As a football enthusiast and a beginner in machine learning, the FIFA World Cup was the perfect “first project”. I decided to build a model which would predict the exact number of goals scored by each team in a game.

A lot of literature which I have found regarding football predictions is focused on predicting the correct tendency (win/draw/loss) and the models are trained on and applied to football league systems such as the English Premier League. The world cup only takes place every four years, which reduces the amount of available data. It is divided into a group stage and a knockout stage and teams which have never encountered each other before often produce surprising results.

I uploaded all relevant files with this repo.

Collecting Data

For data collection, I first checked if there was a database or website which recorded enough data about the past international tournaments. I ended up with transfermarkt.de which has detailed world cup data starting from 2006. I wrote a scraper with scrapy to retrieve the following information

- player market values

- player ages

- team fragmentation (how many different clubs are present in a national team)

- results from past encounters between two teams

- actual results

- gametype (group stage, semifinal,…)

Since there have only been three world cups since 2006, the amount of data is limited (especially the knockout stage games are few). I therefore decided to scrape the European, Asian, African, South American and North American championships as well. This did not require much additional effort because transfermarkt pages all follow the same pattern and no additional scraper was neessary. At the same time, these continental tournaments are the type of football events most similar to the world cup.

A friend of mine helped me with data collection and we found out by chance that the same transfermarkt page would sometimes display different data on different days. We manually removed the inconcistencies to the best of our knowledge. Missing player market values were imputed with the lowest market value within a player’s team.

The final, aggregated dataset can be found here.

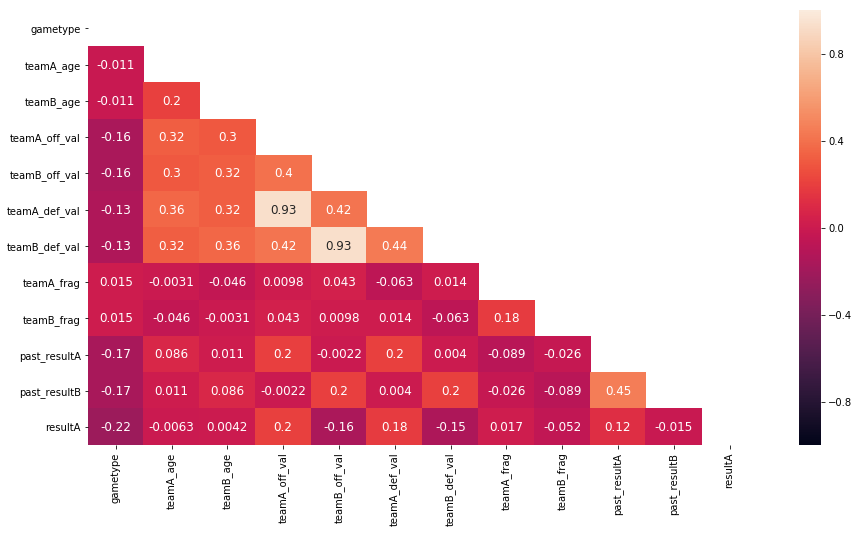

A heatmap plot of the spearman rank correlations shows that a team’s goal count is monotonically related to market values and historic results.

Modelling

I chose to do a negative binomial regression on the obtained data set. The PMF of a random variable \(X \sim Nb(r,p)\) is given by

\begin{equation}

P(X = k) = \binom{r+k-1}{k} p^r (1-p)^k = \frac{\Gamma(r+k)}{\Gamma(r)k!} p^r (1-p)^k \label{eq:pmf}

\end{equation}

In many papers, the Poisson distribution is used to model goal counts. However, the negative binomial distribution can be viewed as a generalization of the Poisson distribution. A random variable \(X \sim Nb(r,p)\) can be seen as a random variable \(X \vert \Lambda=\lambda \sim Po(\lambda)\) where \(\Lambda\) is a gamma-distributed random variable with shape parameter \(r\) and scale parameter \((1-p)/p\).

The PMF can therefore be equivalently written as

\begin{align}

P(X = k) &= \int_0^\infty P(X = k \vert \Lambda=\lambda) \cdot f_{\Gamma(r,(1-p)/p)}(\lambda) \ d\lambda \nonumber \newline

&= \int_0^\infty \frac{\lambda^k \exp{(-\lambda)}}{k!} \cdot \frac{\lambda^{r-1} \exp{\big(-\frac{\lambda p}{1-p}\big)}}{\Gamma(r)\big(\frac{1-p}{p}\big)^r} \ d\lambda \nonumber \newline

&= \frac{p^r(1-p)^{-r}}{\Gamma(r)k!} \int_0^\infty \lambda^{r+k-1} \exp{(-\frac{\lambda}{1-p})} \ d\lambda \nonumber \newline

& = \frac{p^r(1-p)^{-r}}{\Gamma(r)k!} (1-p)^{r+k-1} \int_0^\infty \frac{\lambda^{r+k-1}}{(1-p)^{r+k-1}} \exp{(-\frac{\lambda}{1-p})} \ d\lambda \nonumber \newline

& = \frac{p^r(1-p)^{-r}}{\Gamma(r)k!} (1-p)^{r+k-1} \int_0^\infty t^{r+k-1} \exp{(-t)} (1-p) \ dt \nonumber \newline

& = \frac{p^r(1-p)^{-r}}{\Gamma(r)k!} (1-p)^{r+k-1} (1-p) \Gamma(r+k) \nonumber \newline

& = \frac{\Gamma(r+k)}{\Gamma(r)k!} p^r(1-p)^k

\end{align}

where we integrated by substitution with \(\phi(t)=t(1-p)\).

The mean and variance are given by

\begin{align}

E[X] &= E_{\Lambda}[E_X[X\vert\Lambda]] = E_{\Lambda}[\Lambda] = \frac{r(1-p)}{p} \label{eq:mu} \newline

V[X] &= E_{\Lambda}[V_X(X\vert\Lambda)] + V_{\Lambda}[E_X[X\vert\Lambda]] = E_{\Lambda}[\Lambda] + V_\Lambda[\Lambda] \nonumber\newline

&= \frac{r(1-p)}{p} + \frac{r(1-p)^2}{p^2} = \mu + r^{-1}\mu^2

\end{align}

Here we see that the variance can be larger than the mean for negative binomially distributed random variables. Large \(r\) indicate similarity to a Poisson distribution.

An equivalent representation of the PMF that depends on the mean \(\mu:=E[X]\) instead of the probability \(p\) can be derived if one solves equation \eqref{eq:mu} for \(p\) and plugs it into \eqref{eq:pmf}.

\[P(X = k) = \frac{\Gamma(r+k)}{\Gamma(r)k!} \Big(\frac{r}{\mu+r}\Big)^r \Big(\frac{\mu}{\mu+r}\Big)^k\]

Implementation

The python library statsmodels offers built-in support for negative binomial regression (as part of their GLM module). In statsmodels, the parameter \(\alpha := r^{-1}\) is a hyperparameter that the developer needs to set. This means that it only regresses the mean conditioned on the input data and does not fit the variance. Furthermore, the target variable is only one dimensional, so we would have to regress the mean for both teams separately.

Instead of using statsmodels, I implemented a neural network which would regress the mean \(\mu\) and \(\alpha\) of both teams. In other words, the output layer has 4 neurons. I defined a negative binomial likelihood loss, similar to this implementation in Tensorflow. But instead of using one linear layer (which corresponds to a generalized linear model), I use more linear layers with ReLu functions. This way, the expectation is no longer a linear function of the features but can be learned as a more complex function with nonlinearities.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.nn.functional as F

class NBNet(nn.Module):

def __init__(self,dim_in,h1,h2,dim_out,p_drop=0.2):

super(NBNet, self).__init__()

self.dropout = nn.Dropout(p=p_drop)

self.softplus = nn.Softplus()

self.fc1 = nn.Linear(dim_in,h1)

self.fc2 = nn.Linear(h1, h2)

self.fc3 = nn.Linear(h2, dim_out)

def forward(self,x):

'''

link function score = log(mu)

dispersion alpha > 0

'''

x = F.relu(self.fc1(x))

x = self.dropout(x)

x = F.relu(self.fc2(x))

x = self.dropout(x)

x = self.fc3(x)

muA = torch.exp(x[:,[0]])

muB = torch.exp(x[:,[2]])

alphaA = self.softplus(x[:,[1]])

alphaB = self.softplus(x[:,[3]])

return (muA,alphaA,muB,alphaB)

class NBNLLLoss(nn.Module):

def __init__(self,eps=1e-5):

'''

eps for numerical stability

'''

super(NBNLLLoss, self).__init__()

self.eps = eps

def forward(self,mu,alpha,y):

eps = self.eps

r = 1/(alpha+eps)

s1 = -torch.lgamma(y+r+eps)

s2 = torch.lgamma(r+eps)

s3 = torch.lgamma(y+1)

s4 = -theta*torch.log(r+eps)

s5 = -y*torch.log(mu+eps)

s6 = (r+y)*torch.log(r+mu+eps)

NLL = torch.mean(s1+s2+s3+s4+s5+s6)

if NLL < 0:

raise Exception("NLL cannot be negative for PMF")

return NLL

The learned paramaters \(\mu\) and \(\alpha\) determine a team’s goal distribution. The assumption is that both teams’ goal counts are conditionally independent, so the distribution of a game outcome (the joint distribution of both teams’ goal counts) can be modelled as the product of each team’s goal distribution. In this implementation, I limit the number of goals to a maximum of 10. The outcome distribution is captured in a 11x11 matrix, where rows represent team A and columns team B. The trace of the matrix represents the probability of a draw. The sum of all elements in the strictly upper triangular matrix represents the probability that team A loses. The sum of all elements in the strictly lower triangular matrix represents the probability that team A wins.

import scipy as sc

import numpy as np

class MyUtil(object):

def calc_nb_param(self,mu,alpha):

r=1/alpha

p=r/(mu+r)

return p,r

def calc_nb_probs(self,muA,alphaA,muB,alphaB):

pA,rA=self.calc_nb_param(muA,alphaA)

pB,rB=self.calc_nb_param(muB,alphaB)

nbA = np.vectorize(sc.stats.nbinom)(rA[:,0],pA[:,0])

nbB = np.vectorize(sc.stats.nbinom)(rB[:,0],pB[:,0])

pdfA = np.array(list(map(lambda x:x.pmf(np.arange(11)),nbA)))

pdfB= np.array(list(map(lambda x:x.pmf(np.arange(11)),nbB)))

i=0

probs=np.zeros((pdfA.shape[0],pdfA.shape[1],pdfA.shape[1]))

for row in pdfA:

probs[i,:,:]=np.outer(row,pdfB[i,:])

i+=1

return probs

def tend_acc_nb(self,muA,alphaA,muB,alphaB,y):

probs=self.calc_nb_probs(muA,alphaA,muB,alphaB)

return self.multi_tendency(y,probs)

def multi_tendency(self,y,y_prob):

i=0

result_pred = np.zeros(y.shape[0])

for row in y_prob:

winA = np.tril(row).sum()

winB = np.triu(row).sum()

draw = np.trace(row)

if winA >= winB and winA >= draw:

result_pred[i] = 1

if winB >= winA and winB >= draw:

result_pred[i] = -1

if draw >= winA and draw >= winB:

result_pred[i] = 0

i+=1

act = np.vectorize(self.encode_tendency)(y[:,0],y[:,1])

return np.sum(act==result_pred)/y.shape[0]

def multi_result(self,y_prob,top_n,verbose=False,y=None):

'''

Checks how often the top n results in y_prob contain the true result

'''

N=y_prob.shape[0]

R=y_prob.shape[1]

C=y_prob.shape[2]

count=0

i=0

for row in y_prob:

probs=row.ravel()

idx_ravel = np.argsort(probs)[::-1][:top_n]

idx_unravel = self.get_index(R,C,idx_ravel)

probs = probs[idx_ravel].reshape((idx_ravel.shape[0],1))

if y is None:

print("candidates \n",np.concatenate((idx_unravel,probs),axis=1))

continue

if np.equal(idx_unravel,y[i,:]).all(axis=1).any():

if verbose==True:

print("right prediction for",y[i,:])

print("candidates \n",np.concatenate((idx_unravel,probs),axis=1))

count+=1

elif verbose==True:

print("wrong prediction for",y[i,:])

print("candidates \n",np.concatenate((idx_unravel,probs),axis=1))

i+=1

return count/N

def get_index(self,rows,cols,idx):

col_idx = idx % rows

row_idx = idx // rows

idx = np.column_stack((row_idx,col_idx))

return idx

def encode_tendency(self,x,y,win=1,draw=0,loss=-1):

if x > y:

return win

elif x == y:

return draw

else:

return loss

Results

I evaluated the trained models on a validation set by calculating how accurately the model predicts a game’s tendency (win/draw/loss).

The model for the first match day of the group phase was trained on group stage data from previous tournaments. For the following group matches, the preceding group games of this world cup were additionally included.

For the knockout stage I used knockout stage data from previous tournaments excluding the ones decided by penalty shootouts. I ignored the scenario of penalty shootouts because the dataset only contains the final result and not the results before penalty shootouts. Including the shootouts would skew the goal distribution. Not including them makes it difficult to evaluate the accuracy of the prediction because the model simply isn’t prepared for penalty shootouts.

A total of 6 models were trained: 3 for the group stage, 1 for the round of sixteen, 1 for the quarterfinals, 1 for the semfinals/finals. The table below summarizes the results.

| |

Top-5 Accuracy |

Top-3 Accuracy |

Top-1 Accuracy |

Tendency |

| Group Match 1 |

56.25% |

31.25% |

18.75% |

56.25% |

| Group Match 2 |

50.00% |

37.50% |

12.50% |

68.75% |

| Group Match 3 |

62.50% |

43.75% |

18.75% |

56.25% |

| Round of 16 |

25.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

75.00% |

| Quarterfinals |

50.00% |

50.00% |

0.00% |

75.00% |

| Semifinals/Finals |

25.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

25.00% |

For top-n accuracy, I count a prediction as correct if the actual result is included in the n most probable outcomes. For tendency accuracy, a prediction is counted as correct if the outcome distribution assigns the most probability to the tendency of the actual outcome.

Out of curiosity, I also trained standard sklearn classifiers (Gradient Tree Boosting, Random Forest, Logistic Regression) to see how accurately tendencies can be predicted. The result was an accuracy of roughly 50% for the group stage and 70% for the knockout stage on the validation set.

For Future Reference

The market values of players increase from one tournament to the next. According to statista, the most valuable team in Brazil 2014 was worth 622 million Euros. The most valuable team in Russia 2018 was worth 1080 million euros. If the values change too drastically, the model could end up predicting very high means because the inverse of the used link function, the exponential function, is sensitive to changes of the linear predictor. For example, let \(w = [0.1;0.2;-0.01]^T\) the learned coefficients and \(x_1 = [1;2;5]^T, x_2 = [1;10;5]^T\) two different feature vectors. The predicted mean values differ considerably:

\begin{align}

\mu_1 &= \exp{(w^T x_1)} = \exp{(0.45)} \approx 1.57 \nonumber\newline

&\ll 7.77 \approx \exp{(2.05)} = \exp{(w^T x_2)} = \mu_2 \nonumber

\end{align}

The market values did not increase enough to cause such problems, but for future projects it can be helpful to remove such trends from a time series to prevent instabilities.

Another point for improvement is that the collected data lacks information on a team’s current form. The used dataset includes historical encounters between two teams that face each other in a game, but these encounters are often very sparse. Games that took place years ago are not the best indicator for a team’s current form. For example, Germany looked very good on paper with high market values and good historical records against its group stage rivals. The team still exited this world cup at the group stages. The outcome is not really surprising if one looks at Germany’s most recent test games.

I also got feedback that using every game as two training samples with swapped roles between teams A and B ensures that the learned network won’t depend on the order in which the teams are presented in the sample.

While the above points refer to the quality of the dataset, there is also something that can be improved on model side. Currently, I admittedly don’t know how much I can trust the black box neural network, especially when it outputs results which seem counterintuitive to a seasoned football fan. I calculated the gradients of the predicted average \(\mu\) and \(\alpha\) w.r.t. the input features, but it did not make me trust the model. The paper Understanding Black-box Predictions via Influence Functions introduces the concept of influence functions which identify the training data points that influenced the prediction of a test datapoint the most. I am curious to find out if it can be applied to my football predictions!